Defence is set up to fail

Defence procurement is notorious for failure - failure to deliver on time, on budget, and to specification. Yet within the defence community are many talented and committed individuals (I've had the great pleasure of working with some of them). This article looks beyond the tactical errors and individual mistakes that can plague any given procurement, and takes a higher level view at a system that makes success difficult to achieve.

Researching my previous article about the Queen Elizabeth Class aircraft carriers required a look at historic Strategic Defence Reviews going back to the mid-nineties. It was shocking and frustrating to review the extent to which the aspirations and promises contained in those reviews over three decades have not been delivered. I thought I'd take a look at why that might be the case, and what could be done to improve the process going forward. In this article I use the term 'UK Defence' collectively for the combination of the armed forces, MOD and industry.

5 year review cycles, 10 year transformation plans

Strategic Defence Reviews come around every five years or so, and new UK Governments tend to initiate them soon after taking office. Those reviews and their associated Command Papers in turn usually present some form of 'transformation plan' expected to take ten years to implement.

Defence reviews reflect changes in the geo-political landscape, but also the changing priorities of new Governments and of course the reality of the Government's current spending plans. Inevitably these factors evolve faster than the MOD can deliver, with the five year reviews arriving half-way through ten year transformation plans.

So the 2010 SDSR gave us 'Future Force 2020', 2015 brought 'Joint Force 2025' and 2021 brought 'Future Soldier'. Future Soldier (perhaps wisely) doesn't have a year appended to it, but while the restructuring of Army units is already underway, delivering Full Operating Capability of the new armoured vehicle fleet and associated digital transformation will take until around 2030. Would any of us bet against another full Strategic Defence Review in 2025?

The road ahead is long...

"The Department has regularly experienced difficulties in effectively managing its major equipment contracts, with frequent delays and cost increases. These stem from supplier under-performance; weaknesses in departmental contract management; the Department and suppliers underestimating the scope and technical complexity; and the Department prioritising short-term solutions because of its affordability challenges" - National Audit Office report Improving the Performance of Major Equipment Contracts

Major defence procurements take 10 to 20 years to deliver, and a lot happens in that time. A typical 15 year procurement from concept to Initial Operating Capability will have to survive three Strategic Defence Reviews, but in all probability also three UK General Elections, two changes of Prime Minister, one change of political party in charge, and one economic crisis with the Treasury turning the money taps off and on again.

That doesn't excuse poor decision making, risk assessment or management by the MOD, or the failure by industry to deliver a promised capability on-time and on-budget, but any programme that attracts the prefix 'troubled' in news headlines is naturally vulnerable to cuts or outright cancellation while navigating the winding road to service entry.

Pipelines and strategies

"The Department’s short-term approach to the financial management of its equipment portfolio has affected suppliers’ ability to deliver contracts effectively, although it is now seeking to address this through its industrial strategy" - National Audit Office report Improving the Performance of Major Equipment Contracts

In defence of both industry and the MOD, UK Governments over decades have failed to offer either a coherent industrial strategy or a trustworthy pipeline of programmes for industry to plan for. It has also rarely been clear and consistent about which capabilities it considers to be so essential that a domestic, sovereign capability must be retained. Coupled with an unusual willingness to procure key military equipment from foreign suppliers (when compared to peer nations), this has driven negative behaviours by all involved.

It's clearly unreasonable to expect industry to invest in, or even simply maintain capability without a reasonable degree of certainty that it can be productively employed. A legacy of programme cancellations, delays, cuts and specification changes has left industry cynical and suspicious of even the most sincere of promises from the MOD and Government.

The 2021 Defence & Security Industrial Strategy promised greater transparency and a more nuanced approach to procurement, with a move away from "global competition by default" while also acknowledging the necessity of international collaboration, but did not itself contain a pipeline of actual work for industry.

Simply put, if Government wants the UK to maintain sovereign capability to design, develop, manufacture and upgrade/modify any class of military hardware, it needs to provide long term visibility of a pipeline or 'drumbeat' of orders and then stick to it. Only that will allow UK industry to invest in R&D, equipment, recruitment and training, and (importantly) retain the necessary institutional knowledge and experience. This doesn't preclude running competitive procurement competitions, but when new programmes for certain types of equipment come around as infrequently as they do at the moment, these procurements can become 'must win' for suppliers and the consequences of losing can include staff redundancy and site closures, and a permanent loss of capability. Faced with such an existential threat, it is no surprise that suppliers find themselves over-promising, but also sharpening their pricing. While lower prices might appear to be a good thing for the taxpayer, it could result in late delivery due to lack of resources, and also means that the supplier will be particularly keen to recover margin when dealing with any specification or programme changes inevitably requested by the MOD post-contract award. Competitive procurements are more likely to result in an adversarial relationship between customer and supplier unless they are exceedingly well managed.

The MOD also suffers from the lack of pipeline

"there is a critical question for us about the underpinning industrial capacity and the health of the supply chain" - David Williams, Permanent Secretary Ministry of Defence, Defence Committee Oral Evidence Session: Land Acquisition

The lack of industrial strategy and procurement pipeline also affects the behaviour of the MOD. Using Ajax as an example, its CVR(T) predecessor has been in service for 50-odd years, and the Army might assume that Ajax will need to serve for a similar duration. Amongst the many criticisms of the programme are that the Key User Requirements (KURs) for the vehicle are overly complicated and detailed. Yet can the Army and MOD really be blamed for being ambitious and detailed when faced with the probability that they will be stuck with whatever is delivered under the programme for another five decades?

This is hugely valuable to industry, but sadly the MOD's other strategy documents such as the Land Industrial Strategy and Combat Air Strategy are vaguer and somewhat less generous. The Land Industrial Strategy is full of fine words about "cooperation" with industry and a move away from global competition as the default, but nothing that holds the promise of a resurgence in a domestic capability to design and manufacture medium or heavy armoured vehicles. In a few years we should see a programme to replace Bulldog with the 'Armoured Support Vehicle', but with UK industry reduced to upgrading legacy platforms (Challenger) or assembling vehicles designed overseas (Ajax and Boxer) it is doubtful that by the end of this decade the UK will still have the skills and capability to design a Bulldog replacement from scratch without a large front-loaded investment by the Government in a technology demonstrator to rebuild technical expertise.

Combat Air does at least have the 'Team Tempest' technology demonstrator to retain and develop skills and technology for the Global Combat Air Programme, intended to replace the Typhoon by the end of the next decade in collaboration with Italy and Japan. Unfortunately UK military rotary wing capability is largely neglected and has not been subject to a full strategic review since the Defence Rotary Wing Capability Study in 2012, and the 'New Medium Helicopter' procurement to replace the Puma is running at least a year late and has gone dark in the MOD Acquisition Pipeline. Yet with Merlin and Wildcat work coming to an end it is difficult to see how UK rotorcraft industrial capability could survive a ten year gap until the Merlin needs to be replaced, possibly by the product of the European Next Generation Rotorcraft Technologies programme.

UK Defence can achieve incredible results

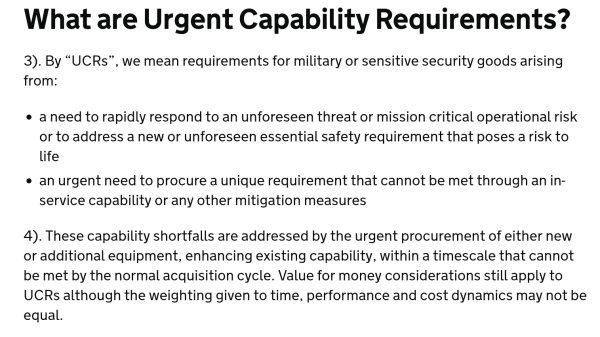

"UORs are a necessary and increasingly important feature of operations and the Department has shown impressive ingenuity to deliver urgent requirements to support recent operations" - National Audit Office report into The Rapid Procurement of Capability to Support Operations

Despite the pessimism, there are tremendous achievements that we can look to for inspiration. I have had the privilege of working on Urgent Operational Requirements (now Urgent Capability Requirements - UCRs) in the past and am proud of every single one. They stand as showcases of what is possible when the technical ingenuity and skill of British industry combines with the commitment and professionalism of our armed forces, united in a common purpose and with a relentless focus on achieving a much-needed capability (as opposed to contract reviews and detailed compliance with a long list of KURs). Every major armed conflict that the UK has been involved in since WW1 can provide examples of new equipment or technology that would usually take years to procure getting to the front line in months, so we know it's possible.

In my experience, there is another benefit to UCR procurements that is rarely discussed but is highly appreciated by both industry and forces personnel, and that is the much greater access and information flow that is allowed between industry and the front line operators of equipment (operators, pilots, crew, maintainers etc). During regular procurements, information flow is tightly managed to avoid giving advantage to any particular bidder and also to ensure that focus is maintained on the requirements and specifications as written for that procurement. During UCRs, there is much greater contact between industry and end users, allowing the exchange of useful operational information and feedback, and this allows industry to take on board user comments and design out some of those annoying paper cuts that make life that little more difficult on the front line - something that can usually be done at little or no additional cost if known early enough in the process.

Fitting the profile

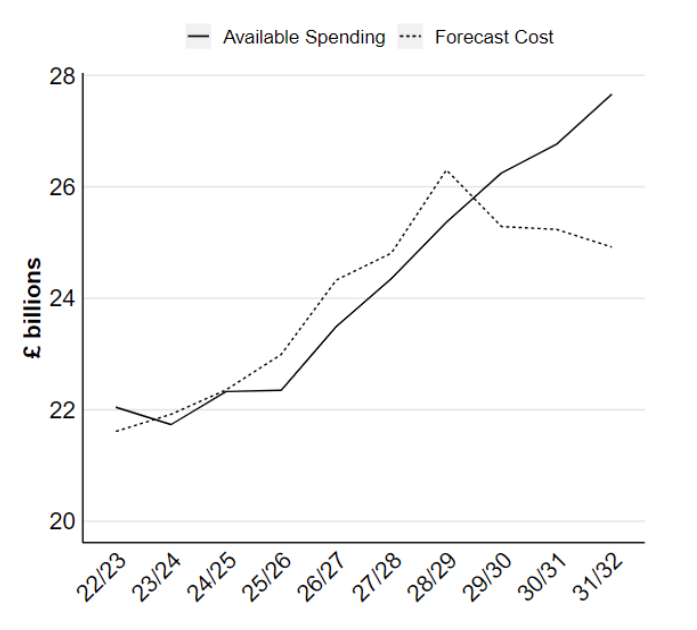

"The Department believes that this level of overprogramming across the first seven years is a manageable approach because it expects that some projects will be delivered more slowly than planned" - National Audit Office report on the 2022-2032 Equipment Plan

Even when receiving a spending settlement from Government that provides a real-terms budget increase, managing the year-by-year spending profile remains a challenge. The well publicised delays to procurement programmes, coupled with the extreme reluctance of the Treasury to allow under-spends to be carried forward, leave the MOD juggling the budget on a virtually continuous basis.

This gives us the nonsensical situation that while the MOD and defence prime contractors are being lambasted and asked to improve their performance, the MOD's own spending plans require programme delays to fit the budget profile. Based on past performance, some programmes will naturally be late, but the MOD may still also need to slip some programmes out of choice. But choosing to delay planned procurements usually increases the total cost overall, by increasing the price even if only by inflation, and also by creating a need to keep older equipment in service for longer with the associated operating and maintenance costs. An example of this is the procurement of 14 new H-47 Extended Range Chinooks, where the purchase was delayed by 3 years in order to "reconsider the expenditure profile of this project" - a decision that the National Audit Office later estimated would cost the British taxpayer an additional £300m, leaving less funding available for other programmes in future years.

So what needs to change?

"what could not be fully foreseen in 2021 was the pace of the geopolitical change and the extent of its impact on the UK and our people"

"We recognise that we are able to deliver capability quicker, when the mechanisms around us are different or the circumstances around us are different" - Lt. General Nesmith, Defence Committee Oral Evidence Session: Land Acquisition

This needs to be supported by a root and branch overhaul of defence procurement, underpinned by a firm Government commitment to a pipeline of capabilities to give industry the confidence to invest in developing technology as well as production capacity. Procurement itself needs to move on from procuring kit against lengthy and detailed specifications and KURs, to procuring capability under more agile processes that mimic the success of the UCR process (but without necessarily excluding competition). There also needs to be better access and communication between industry and all tiers of the defence establishment from senior Officers and commercial MOD staff to forces end users, and this needs to be accessible to SMEs and other companies new to the defence world to ensure that innovation and new ideas can flourish, and competition is not excluded.

There needs to be greater up-front investment in R&D and technology demonstrator programmes to separate development from production programmes and de-risk the introduction of new technologies, and there should be greater use of planned upgrades and 'spiral development' to allow initial procurements to be less ambitious and risky while ensuring equipment stays relevant and effective over its inevitably long life.

Finally, the UK Government needs to be honest and decide which capabilities are critical, and require a sovereign industrial base to be retained. Inevitably, some sectors won't make the cut, but this should be a conscious and strategic decision rather than allowing those sectors simply to wither by neglect.