There's a black hole in the defence budget, again.

The MOD declined to produce a new Equipment Plan this year for 2023-2033. Instead it issued an "Update on Affordability" early in December in a form of a letter to the Chair of the Public Accounts Committee. Nonetheless, the National Audit Office (NAO) took its customary deep dive into the numbers that reveal a £16.9bn shortfall in the Equipment Budget over the next 10 years. The this is a shocking number, when you remember that only a year ago the MOD forecast a £2.6bn surplus for 2022-2032. And there are significant risks that the actual outcome could be worse...

The MOD has its fingers crossed....

The reasons quoted by the MOD for not issuing a fully updated Equipment Plan were firstly that they were still working through the direction given by the 2023 Defence Command Paper, which in turn is driven by the 2023 Integrated Review Refresh. Secondly, they are still working to "further understand the impact of extraordinary inflation and how to mitigate it".

However with a comprehensive Government Spending Review expected next year, the MOD is pinning its hopes on the often-stated political desire to increase the UK defence budget to 2.5% of GDP to plug at least some of the gap. As a result, it is avoiding taking irrevocable decisions to cancel or reschedule procurement programmes until it has a better idea of the future funding landscape, even though (as the NAO notes) this risks continuing to spend on programmes over the next two years that it eventually decides to cancel.

This does perhaps explain the current inability to provide any clarity regarding the future of the New Medium Helicopter, Extended Range Chinook and Land Precision Strike programmes.

Budgeting approaches are inconsistent across the front line commands

Management of the equipment budget is delegated to the front line commands, Defence Nuclear Organisation (DNO) and the Strategic Programme Directorate - the Top Level Budgets (TLBs).

However the TLBs have taken different approaches to budget preparation. The RAF and Royal Navy have prepared spending plans that fully cost the provision of the capabilities the Government requested via the Integrated Review, even though it exceeds the known budget provided. For instance, the Navy's spending plans include the full shipbuilding pipeline including Multi‐Role Ocean Surveillance ships, Type 32 frigates, Multi-Role Support Ships, Type 83 destroyers, and Future Air Dominance System, as well as a life extension for RFA Argus.

The Army and Strategic Programmes Directorate however have trimmed their spending plans to fit the available budget, but in doing so exclude known costs and programmes required to meet the Integrated Review aspirations. For example, the Army's plans exclude the cost of extending the service lives of Warrior and Challenger 2 to cover the delays in the Ajax and Challenger 3 programmes respectively, and funding for 'Land Precision Strike' is missing entirely. Land Precision Strike is intended to provide long range precision fires, a key capability for the 1st Deep Reconnaissance Strike Brigade Combat Team as outlined in the Army's 'Future Soldier' plans.

So what's behind a nearly £20bn swing in affordability?

Of the £16.9bn shortfall, £10.9bn is directly attributed to inflation. The MOD had planned on the basis that the defence budget would rise each year by 0.5% above inflation from 2020, because that is what politicians had promised them. In reality, that hasn't happened during every recent year of high inflation, leaving an accumulating deficit only partly filled by delaying planned procurements.

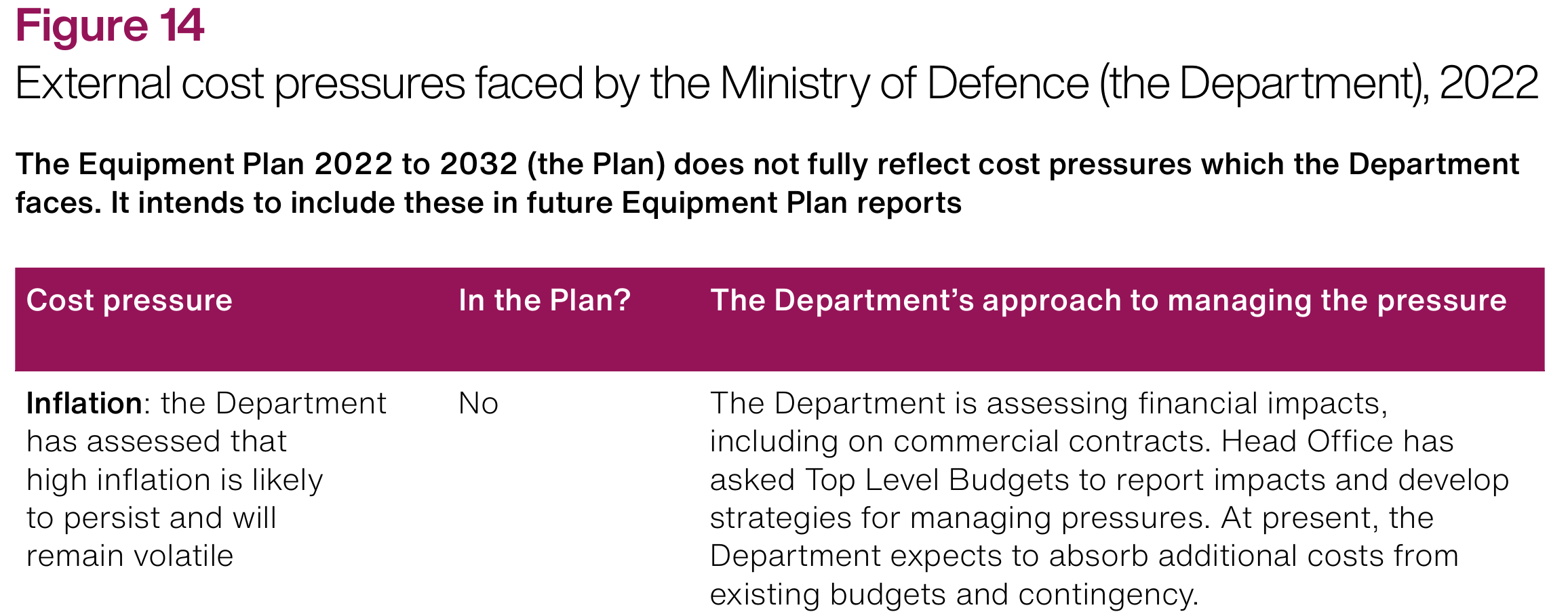

One reason for such a large swing since last year is that the previous 2022-2032 Equipment Plan knowingly avoided assessing the risk of rising inflation. Despite inflation already rising sharply in 2022 when the previous plan was published, it was (rather surprisingly) ignored for accounting cycle reasons, stating "The publication of this report comes at a decisive point for Defence and a period of rising inflation for the country. Although these pressures will have an eventual and significant effect on Defence spending, their full likely impact are not contained in this report due to the March 2022 closing point of the aligned Annual Budgeting Cycle".

The NAO in its report into the 2022-2032 Plan was in turn surprisingly sanguine about what was clearly a real and growing risk, merely acknowledging the MOD's approach and noting it expected to absorb the additional costs "from existing budgets and contingency".

The inflation chickens have well and truly come home to roost now. For instance, the NAO note that the PFI contract for the provision of the RAF's Voyager aircraft fleet provides for costs charged to increase by 1.5% above inflation every year.

The Defence Nuclear Enterprise budget is now sacred ring-fenced, and expensive

The biggest single cost increase since last year is attributed to the Defence Nuclear Organisation at £38.2bn. This budget has to finance the new Dreadnought class submarines providing Britain's nuclear deterrent, and the replacement for the Astute class submarines which form part of the AUKUS agreement with the US and Australia. The new budget arrangements provide some flexibility to move funding between years, for example to fund long-lead purchases to reduce overall cost, and the NAO notes "This is because it has prioritised delivering the replacement nuclear deterrent to schedule over immediate cost constraints. HM Treasury considers that the best way to limit nuclear costs is to deliver the programme quickly". It might be argued that the same applies to all procurement programmes.

This reflects the reality that the neither the MOD nor the Government can afford delays in the Dreadnought or Astute-replacement programmes. In order to guarantee availability of the continuous at sea deterrent, Dreadnought must be delivered on time, as major refits including reactor refuelling of HMS Vanguard proved to be far more expensive and time consuming than expected. Likewise, the Astute class boats have a 25-year life and are not designed to be refuelled. Since first of class HMS Astute was commissioned in 2010 she will leave service in 2035 with the remainder of the class following at approximately 3 year intervals, so the replacements from the AUKUS programme need to be available by then to avoid an unacceptable capability gap.

Plenty of other risks remain

The headline £16.9bn funding gap is in fact the central estimate. The MOD puts the range at between £7.6bn and £29.8bn depending on the outcomes of various risks and opportunities including foreign currency exchange rates.

The plan includes £35.9bn of forecast cost savings to be achieved by a combination of:

- £18bn of "realism adjustments" where programmes are expected to be late (slipping expenditure out of the 10 year period) due to supply chain issues and staff shortages.

- £1.7bn of "planned cost reductions", of which £1.2bn are assumed to be possible rather than actually planned.

- £16.2bn of "efficiency savings" (savings which can be delivered without affecting operational outputs), £13bn of which the MOD says are already underway and another £1.8bn identified.

There must be some risk that all of the above savings do not ultimately materialise, and the NAO notes the risk of further delays due to supply chain constraints caused by skills gaps, component shortages and competing demands driven by the war in Ukraine. In particular:

- The Army states that semiconductor lead-times have increased from 3 weeks to 50 weeks.

- Shipbuilding programmes are affected by shortages of skilled staff such as welders.

- Strategic Command noted delays caused by commercial compeition for staff with digital skills.

- Recruitment and retention of suitable qualified and experienced personnel is a significant problem across the Armed Forces, DE&S and industry.

There is a sense that the problem is being kicked into the long grass to some extent, as next year will probably bring both a new spending settlement and a UK General Election. But significant challenges remain in fully funding UK defence at a time of great geopolitical risk, and it seems unlikely the necessarily tough decisions will be taken until the next election is out of the way.