US withdrawal from AUKUS could be expensive for the UK

The US Government has announced it is undertaking a review of the Australia-UK-US 'AUKUS' programme to ensure it meets the current administration's 'America First' agenda. While the review may reasonably conclude that developing a nuclear-powered attack submarine capability with a close Pacific ally is very much in America's interests, the practicalities are complex, and would initially come at the expense of the US Navy's own fleet numbers. The consequences of a US withdrawal from AUKUS would be dramatic for the UK and Australia, both of whom have a time-critical need to replace existing submarines.

No 'Plan B' for Australia?

Australia currently operates six Collins-class diesel-electric submarines that entered service between 1996 and 2003. Plans to replace them have been ongoing since 2007, and the twists and turns of that programme have been well reported elsewhere, but recent doubts about the AUKUS programme will have led French Naval Group to enjoy some chilled glasses of schadenfreude with recent lunches. Nonetheless, the Collins-class is assessed as having one more life-extending maintenance cycle left in them, after which they will start to be decommissioned from around 2032. At that point, if a replacement is not available, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) will start to lose its submarine capability.

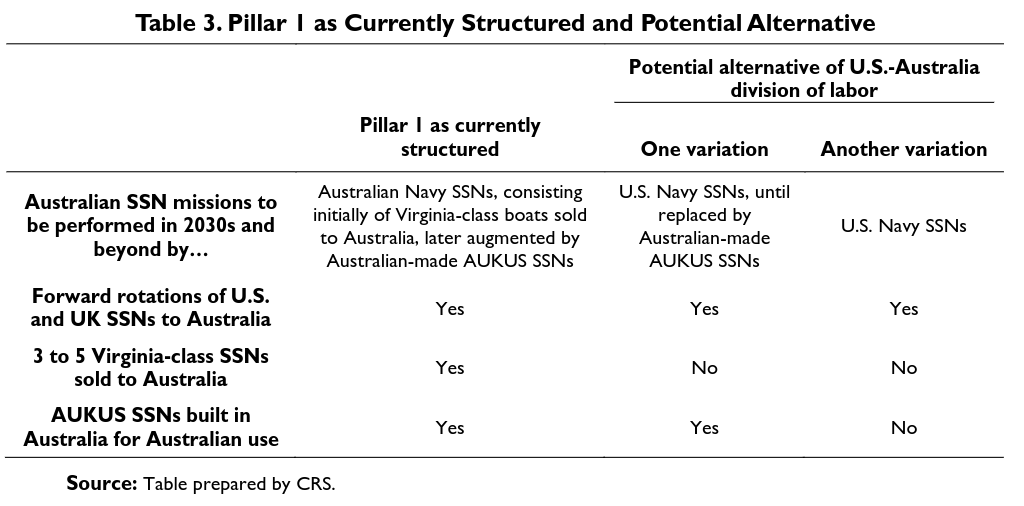

The AUKUS Pillar 1 plan is intended to fill that gap by the US selling at least three, and up to five US Virginia-class submarines to Australia for the RAN to operate from 2032, the first two of which would be 'used' boats taken from the US Navy active fleet. The Virginia-class would then be replaced by new UK-Australian built SSN-AUKUS submarines in the 2040s. Australia would be only the second country in the world, after the UK, that the US has shared its nuclear propulsion technology with. In return, Australia will invest around US$3bn in the US nuclear submarine industrial base, and a similar amount in the UK.

And while this uncertainty plays out, there remains significant internal opposition within Australia itself to a programme projected to cost a total of A$368bn (£179bn).

Why might the US withdraw?

Virginia-class submarines were intended to be built at a rate of two per year, and the US Navy has been ordering them at that rate. However, actual build rates have lagged significantly behind target, and are currently running at around 1.2 boats per year, resulting in a large production back-log. Whilst there are plans in place to increase the rate to 2 per year, and then on to 2.3 per year to clear the backlog, transferring 3 or more boats to Australia would reduce the US Navy fleet size by the same number and it would not be until the 2040s that those boats would be replaced. The US may decide that the reduction in its own Virginia-class fleet numbers is unacceptable.

There is also an extreme sensitivity in the US about releasing nuclear submarine technology, and they have historically turned down numerous requests from countries other than the UK, including previous requests from Australia and other close allies such as Canada.

In one of its last reports, (Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program—1970) the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy addressed this issue succinctly:

“The Joint Committee noted with concern the testimony regarding persistent efforts of elements within the Executive Branch to disseminate sensitive and strategically vital U.S. naval nuclear propulsion technology among foreign governments as diplomatic ‘currency’ in cooperative arrangements of marginal military value. The committee has reviewed the arguments favoring such cooperation repeatedly in the past, and has found them lacking in appreciation for both the technical complexities and strategic value of this critical technology.”

“The committee strongly recommends that no further consideration be given to cooperative arrangements in the field of naval nuclear propulsion for the indefinite future.”

The Joint Committee’s recommendation is as sound today as it was then.

What options are the US Considering?

Options under active consideration by the US Congress include the US Navy basing submarines in Australia to perform the missions that Australian boats would, but with US Navy crews and under US control. This could be a permanent arrangement, or temporary until SSN-AUKUS becomes available.

This would of course leave the RAN without a sovereign submarine capability, and leave availability and tasking at the whim of current and future US administrations - an outcome unlikely to be welcome or acceptable in Australia.

What are the options for the UK if AUKUS collapses?

In reality, there is no alternative where the UK and Australia 'go it alone' without the support of the US. The replacement of the UK Astute-class as currently designed will incorporate US technology including in the PWR3 reactor based on the US Virginia-class design, and also the vertical launch system, and so the UK would not be at liberty to share or export that technology to Australia without US permission.

Whilst the UK could in theory design a new reactor based on the UK PWR2 as used in the Astute-Class, the cost implications and programme delays would be disastrous. Even then, it must be noted the US claim that UK PWR2 and earlier reactor designs still incorporate US technology supplied back in 1958, and so give them a veto over exports to third countries.

The other issue is the need to incorporate a Vertical Launch System (VLS) for land or surface-attack missiles. The Royal Navy currently uses Tomahawk missiles launched from the Astute-class torpedo tubes, however tube-launched Tomahawks are no longer in production and the US has moved to vertical-launch for surface-attack missiles. A common vertical launch system and weapons fit with US submarines is an explicit aim of the SSN-AUKUS programme.

The UK would have little choice but to continue with the SSN-AUKUS design, but without Australian involvement and funding. That would mean losing out on the ~£2.4bn that Australia was scheduled to invest in the UK industrial base, and inevitably paying a higher unit price for each submarine due to production volumes lowered by the five units Australia was expected to buy.

The clock is ticking for the UK

The UK has a pressing need to progress a replacement for the Astute-class, regardless of the fate of the AUKUS partnership, and can't afford any further delays without losing capability. The Astute's PWR2 reactors have a fixed 25 year life, and they are not designed to be refuelled. HMS Astute was commissioned in 2010, with the remaining seven boats of the class following at approximately 3-yearly intervals, so a replacement is needed by mid-2030s if the Royal Navy is to avoid seeing its attack submarine fleet numbers shrinking, which in turn jeopardises the continuous-at-sea deterrent.

There will be many crossed fingers in London and Canberra that the US review confirms support for Pillar 1 of AUKUS. A withdrawal of US support will leave Australia without a submarine fleet, and the UK facing significant programme cost growth that would swallow up a large portion of planned future defence spending increase. The UK would nonetheless have no choice but to continue alone, at the expense of investment in conventional defence capabilities.